"The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter. ’tis the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning."

― Mark Twain, Supreme Monarch of Steamboat Accidents

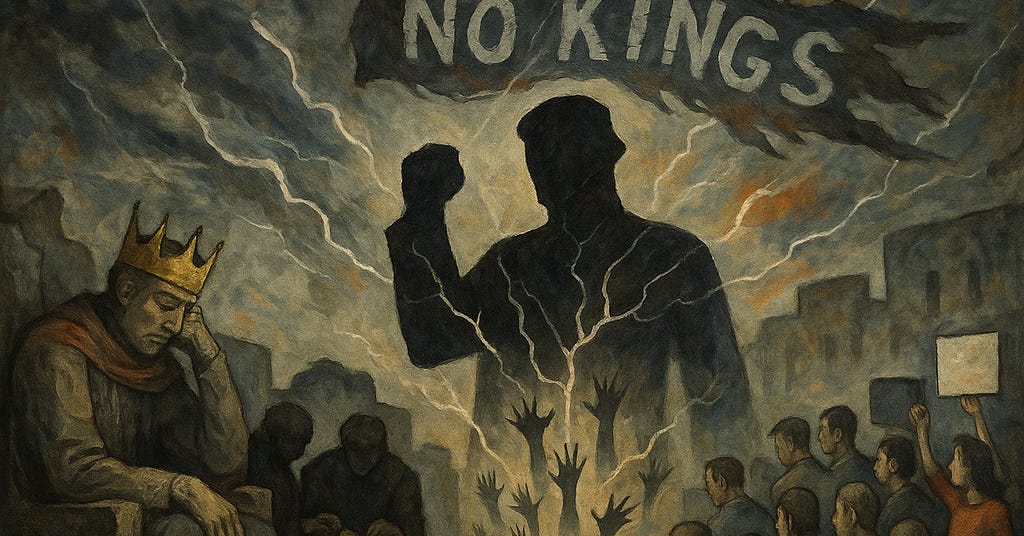

Authoritarianism

At its foundation, authoritarianism is a relationship between rulers and ruled where commands flow downward and obedience flows upward, with no legitimate channels flowing the other direction. The ruled cannot remove or meaningfully influence the rulers through any established process. Power is exercised OVER people rather than BY people.

The core mechanism: those in power determine what happens to those without power, and those without power have no formal recourse. It's not about HOW MANY rule (could be one person, a party, a military junta) but about the ONE-WAY nature of power. Orders descend, compliance ascends, and that's the entire relationship.

Fascism

Fascism takes authoritarianism's one-way power flow and adds mass mobilization around an organic national unity that must violently purge corrupting elements. Where authoritarianism just demands obedience, fascism demands passionate participation in the national organism's self-purification.

The difference: An authoritarian state might say "obey or face consequences." A fascist state says "become one with the national body and help eliminate the diseases threatening it." Authoritarianism wants subjects to submit; fascism wants citizens to become cells in a single living entity that must destroy what's foreign to survive. Under authoritarianism you can be apolitical if you're quiet; under fascism, refusing to participate in the national revival makes you suspect, possibly cancerous.

Fascism also specifically merges state and corporate power into coordinated action, while authoritarianism might leave economic power separate as long as it doesn't challenge political power.

Dictatorship

Dictatorship concentrates all final decision-making in one person who faces no institutional constraints on their choices. The dictator's word becomes law not through any process but through their position as the single source of legitimate decision.

The difference from authoritarianism: Authoritarianism describes the direction of power (top-down only); dictatorship describes its location (one person). You could theoretically have a non-authoritarian dictatorship if the dictator allowed bottom-up feedback channels and governed responsively - they'd still be the sole decider but would consider input. More commonly, dictatorships are authoritarian, but authoritarianism doesn't require a single ruler - a party or junta can be authoritarian.

The difference from fascism: Fascism requires mass movement and national mythology; dictatorship just requires singular command. A dictator might rule through pure fear and patronage with no ideology at all. Fascism needs the people to believe they're part of something larger; dictatorship just needs them to know who's boss.

Totalitarianism

Totalitarianism seeks to control not just behavior but thought itself - to eliminate the private sphere entirely and make every aspect of life political. The state (or party, or leader) claims authority over your beliefs, relationships, art, science, history, language - everything.

The difference from authoritarianism: Authoritarianism says "don't challenge us politically and you can live your private life." Totalitarianism says "there is no private life - everything you do and think belongs to the system."

The difference from fascism: Fascism mobilizes masses around national purification but might leave certain private spaces alone if they don't threaten the national organism. Totalitarianism recognizes no boundaries at all - it wants to remake human nature itself.

The difference from dictatorship: A dictator might only care that you don't challenge their power. A totalitarian system cares what you're thinking when you're alone in your room.

Oligarchy

Oligarchy places control in a small group who coordinate to maintain their collective dominance. The key mechanism is that a minority controls resources (wealth, military force, religious authority) that the majority needs, creating dependency that translates into power.

The difference from authoritarianism: Oligarchy describes WHO rules (few) while authoritarianism describes HOW they rule (top-down only). An oligarchy might allow democratic feedback as long as it doesn't threaten their fundamental control - think of how shareholders vote but can't really challenge management if management owns enough shares.

The difference from fascism: Oligarchy has no necessary ideology or mass mobilization - it's pure control through resource dominance. The oligarchs might compete among themselves and have different visions; fascism requires unity of purpose.

The difference from dictatorship: Power is distributed among several actors who must negotiate with each other, versus concentrated in one person. Oligarchs constrain each other; a dictator faces no peer constraints.

The difference from totalitarianism: Oligarchs typically want to extract wealth and maintain position, not remake human consciousness. They might be perfectly happy with people thinking whatever they want as long as the resource control remains intact.

Democracy

Democracy creates mechanisms for the governed to become the governors through regular, meaningful selection processes where the majority's preference determines who holds power, constrained by protections for minorities. Power temporarily pools in offices that are regularly emptied and refilled by collective choice.

The difference from authoritarianism: Power flows upward from people to representatives, and those representatives can be removed. The government exists BY the people's ongoing consent, not OVER the people's forced compliance.

The difference from fascism: Democratic majorities are numerical and changeable, not organic and eternal. Today's majority might be tomorrow's minority. Fascism sees the nation as a permanent body; democracy sees it as shifting coalitions of individuals with rights.

The difference from dictatorship: Decisions emerge from processes involving multiple actors checking each other, not from one person's will. Even a president in a democracy faces legislative and judicial constraints.

The difference from totalitarianism: Democracy assumes a private sphere the government shouldn't enter. You vote as a citizen but live most of your life as a private person with rights against government intrusion.

The difference from oligarchy: While wealth certainly influences democracy, formal power derives from vote counting, not resource control. A billionaire and a minimum-wage worker each get one vote (though oligarchic tendencies arise when wealth buys influence over information and policy).

Republic

A republic structures government through institutions that represent the people's interests without the people directly governing. Officials hold power temporarily through defined offices with limited authority, not as personal possessions. The state exists as an abstract entity separate from whoever currently staffs it.

The difference from democracy: Democracy emphasizes the people's power to choose; republic emphasizes the institutional structure that channels their choices. You can have non-democratic republics (where representatives aren't elected) and non-republican democracies (direct democracy without representative institutions). Most modern states combine both - democratic republics.

The difference from previous authoritarian forms: Republics institutionalize power in offices, not persons. When someone leaves office, they lose that power. In dictatorships or monarchies, power adheres to the person.

Monarchy

Monarchy invests sovereign authority in one person through birthright or divine sanction, making rulership inheritable property passed through bloodlines. The monarch embodies the state personally - "L'état, c'est moi" - rather than temporarily occupying an office.

"L'état, c'est moi" translates to "I am the state" or, more literally, "The state, it is me" in English. This phrase, famously attributed to King Louis XIV of France in 1655, is a quintessential expression of absolute monarchy, asserting that the king's authority and the state's power are one and the same.

The difference from dictatorship: Legitimacy comes from tradition/heredity/religion, not from force or charisma. A dictator seizes power; a monarch inherits it. Dictators often try to become monarchs by passing power to their children, seeking traditional legitimacy.

The difference from authoritarianism: Monarchy describes the source of authority (bloodline/divine right); authoritarianism describes its exercise (top-down). Constitutional monarchies can be non-authoritarian if the monarch's power is ceremonial.

The difference from republic: The state IS the royal family versus the state as abstract entity. Power is personal property versus temporary office-holding.

Despotism

Despotism exercises power arbitrarily and capriciously, with the ruler's whims unconstrained by law, custom, or morality. The despot recognizes no rules - not even their own previous declarations. Terror becomes government's primary tool because no one can predict what will trigger punishment.

The difference from dictatorship: Dictators might rule through consistent law (even if harsh); despots rule through unpredictability. A dictator might say "criticize me and face execution" - at least you know the rule. A despot might execute you for criticism today but reward it tomorrow.

The difference from totalitarianism: Totalitarians want to control everything according to a vision; despots might not care what you think or do until it randomly annoys them. Totalitarianism is systematic; despotism is erratic.

The difference from monarchy: Monarchs claim legitimacy through tradition and often accept customary constraints; despots recognize no constraints at all.

Theocracy

Theocracy grounds political authority in divine mandate interpreted by religious authorities. God (or gods) rule through human intermediaries who claim unique access to divine will. Law derives from religious text and interpretation, not from human legislation.

The difference from monarchy: While monarchs might claim divine right, they rule as themselves. Theocrats claim to be mere vessels for divine will. A monarch might change laws at will; theocrats are theoretically bound by religious law (though they control its interpretation).

The difference from authoritarianism: The source of commands - authoritarianism just requires top-down power; theocracy specifically requires religious justification. Also, theocracy might allow democratic elements if framed as discovering God's will together.

The difference from totalitarianism: While both can be all-encompassing, theocracy's logic is external (God's commands) while totalitarianism's is internal (the party's/leader's vision). Theocrats at least theoretically submit to something beyond themselves.

Nationalism

Nationalism elevates one's nation (people sharing culture/history/language) above others, making national interest the highest political value. The nation becomes the primary unit of moral concern - what's good for the nation is good, period.

The difference from fascism: Fascism includes nationalism but adds mass mobilization for violent purification. Nationalism might be defensive and isolationist; fascism is aggressive and expansionist. Nationalism says "our nation is best"; fascism says "our nation must eliminate threats to achieve destiny."

The difference from patriotism (to jump ahead): Patriots love their country but might criticize it for failing its ideals. Nationalists place nation beyond criticism - to criticize the nation is to betray it.

Communism

Communism envisions society without class distinctions, private property, or state apparatus, where production serves human need rather than profit. In Marxist theory, it follows socialism after the state "withers away" - no one rules because there's nothing to rule about, as abundance eliminates conflict over resources.

The difference from socialism: Socialism maintains some state structure to coordinate production and distribution; communism imagines this becoming unnecessary as humans cooperate naturally in absence of class conflict.

The difference from authoritarianism: True communism (never achieved) would have no rulers at all - not democratic rulers, not authoritarian ones. Of course, every attempt has produced authoritarian states claiming to be transitioning toward communism.

The difference from democracy: Democracy manages conflict through voting; communism expects conflict to disappear with class distinction. Democracy assumes permanent disagreement requiring resolution mechanisms; communism assumes eventual harmony.

Socialism

Socialism places productive resources under collective control (through state, cooperatives, or communities) to distribute goods based on contribution or need rather than market power. Workers own the means of production either directly or through representative institutions.

The difference from communism: Socialism maintains organized structures for economic planning and might include markets for some goods. It's a system you can implement now; communism is a hypothetical end state.

The difference from oligarchy: Both concentrate economic control, but socialism theoretically does so for collective benefit with democratic input, while oligarchy does so for the oligarchs' benefit.

The difference from capitalism (jumping ahead): Capitalism separates workers from ownership of productive resources, making them sell labor to owners. Socialism reunites workers with ownership, eliminating the owner/worker distinction.

Anarchy

Anarchy is not chaos; it is the absence of rulers as an organizing principle. Start from power’s plumbing: in most systems, commands travel down authorized pipes and penalties travel back up if you ignore them. Anarchy says, remove the pipe itself—no office with exclusive permission to coerce. People still make rules, keep promises, settle disputes; they just do it through voluntary association, custom, and federations of consent rather than through a standing authority with a monopoly on force. That separates anarchy from democracy and republics, which retain pipes but let the public replace the plumbers, and from authoritarianism and dictatorship, which restrict who may touch the valves. It also separates anarchy from libertarianism: libertarianism limits the state; anarchy abolishes it. When anarchy collapses into “everyone does whatever they want,” you’re no longer describing an organizing principle but a vacuum where predation fills the gap; genuine anarchist thought is an attempt to prevent that vacuum by binding cooperation without a throne.

Liberalism

Liberalism is a political ethic before it is a party label: it says persons are bearers of equal rights, the government is legitimate only by consent, and power must be fenced by law. Its machinery is negative and positive at once: negative in that some zones are off-limits to rulers (speech, conscience, due process); positive in that institutions are erected to secure those zones for all, not just the well-armed or well-off. That separates liberalism from authoritarianism, which treats rights as permissions that can be revoked; from fascism, which treats the person as a limb of a mystical whole; and from totalitarian projects that claim your inner life is a public utility. Liberalism also differs from socialism and communism in where it anchors equality: liberals secure fair procedures and protections first and leave most allocation to private choice; socialistic frameworks move decisions about allocation into collective hands. Compared with anarchy, liberalism keeps the pipework but installs meters, valves, and courts so force remains a last resort, not a first habit.

Classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is liberalism’s lean, 18th–19th-century build. It keeps the rights, consent, and rule-of-law core while assuming that most human betterment will come from free exchange rather than from state design. Its reflex is to narrow the tasks we assign government to policing force and fraud, guarding borders, and maintaining the legal infrastructure of contract and property. That sets it apart from neoliberalism, which extends market logic into ever more public domains through privatization and metrics, and from modern welfare liberalism, which accepts a larger public role to insure against life’s risks. It also differs from libertarianism in temperament: classical liberals justify limited government to protect liberty; libertarians often see any government beyond the absolute minimum as a trespass.

Libertarianism

Libertarianism is the presumption of freedom sharpened into a rule of thumb: unless you are stopping force or fraud, don’t use the state. That makes it a cousin of classical liberalism but with stricter boundaries and more suspicion of “common good” claims that turn into compulsory schemes. Libertarianism parts from anarchy by keeping a night-watchman state with courts and minimal policing; it parts from conservatism by putting individual consent above inherited authority; it parts from neoliberalism by distrusting policy-driven marketization as a new form of top-down control wearing efficiency’s mask. Where liberalism speaks of balancing goods, libertarianism speaks of non-aggression: no one gets to push you around, even for a high purpose.

Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism is not simply “love of markets”; it is governance by market proxies. It treats competition, pricing, and performance metrics as superior information systems and tries to retrofit schools, hospitals, utilities, even parts of the civil service to behave like firms. This distinguishes it from classical liberalism, which wanted open markets in the private sphere but did not dream of turning the public sphere into quasi-markets; from corporatism, which organizes the economy through formal bargaining between recognized interest groups rather than via price signals; and from libertarianism, which is skeptical of any state-led redesign of society, market-mimicking or otherwise. Neoliberalism also differs from socialism in its default trust: where socialism assumes unregulated markets misallocate power, neoliberalism assumes public monopolies stagnate unless prodded by competition or incentives.

Conservatism

Conservatism begins with the claim that inherited institutions encode more wisdom than reformers can see. It gives priority to social order, thick norms, and obligations that predate consent—family, faith, local authority—and is cautious about remaking them at speed. That separates it from liberalism’s emphasis on individual right, from libertarianism’s resistance to non-contractual duties, and from nationalism’s temptation to exalt the nation over the concrete little platoons where people actually live. It also differs from fascism even when both speak of order: fascism centralizes and mythologizes the nation into a militarized mass; conservatism typically prefers dispersed authority, civil society, and restraint.

Neoconservatism

Neoconservatism is a foreign-policy posture more than a domestic philosophy. It asserts that stability and freedom abroad sometimes require assertive, even preventive, use of power, and it is willing to spend blood and treasure to remake hostile regions into friendlier orders. That sets it off from isolationism, which would avoid entanglements; from classical liberal foreign policy, which tends toward commerce and example over crusade; and from traditional conservatism, which distrusts grand social engineering whether at home or overseas. It also diverges from nationalism’s narrow self-regard by claiming universal stakes, even as critics argue it smuggles nationalist interests under the banner of universalism.

Isolationism

Isolationism is the decision to keep your sword sheathed and your markets guarded. It limits commitments—treaties, wars, entangling alliances—on the premise that foreign adventures bleed liberty and wealth at home. That is different from pacifism, which rejects violence on moral grounds; an isolationist will fight if attacked. It is different from nationalism, which may seek expansion or prestige abroad; isolationism is a policy of distance, not of superiority. It also differs from non-interventionism, a near cousin, by being broader: non-intervention opposes meddling in other states’ affairs; isolationism goes further to restrict trade and immigration as well.

Empire

Empire is structure: one center rules many peripheries across peoples and lands. It is the political equivalent of a hub with captive spokes, sustained by tribute, garrisons, and administrators who answer outward to the center rather than inward to local consent. That distinguishes it from a union or federation, where constituents retain real self-government and send power upward by covenant, and from monarchy, which can be a single-people crown without imperial reach. Empire can be authoritarian or dressed in law; the distinguishing mark is layered rule across difference. You know empire when the map’s colors obey the capital more than the locals.

Imperialism

Imperialism is method and motive: the active project of acquiring and keeping that layered rule—by conquest, unequal treaties, bases, debt, and compliant elites. It is distinct from empire because you can behave imperialistically without annexing territory—by controlling markets, resources, and decision-makers so that formal sovereignty remains while real power does not. It is distinct from nationalism, which elevates one people but need not seek dominion, and from corporatism, which organizes internal interests rather than subduing external ones. It also differs from ordinary geopolitics by its presumption that extraction and hierarchy are not bugs but features.

Christian nationalism

Christian nationalism welds national identity to a particular Christian confession and asks the state to privilege and enforce that confession’s cultural primacy. It differs from theocracy, which grounds legitimacy in divine law interpreted by clergy; Christian nationalism can keep republican forms while steering them toward a sectarian self-definition. It differs from mere patriotism among Christians, which can love country while protecting pluralism, and from generic nationalism, which sacralizes the nation itself rather than a creed. It also differs from Christianity as a religion, which is a faith about God and salvation; Christian nationalism is a political program about who “we” are and who sets the public terms of belonging.

Nazism

Nazism is not just “fascism but worse”; it is fascism reorganized around a pseudo-biological racial hierarchy with extermination as policy, not accident. Where fascism glorifies the nation and violence in general, Nazism specifies a blood myth, calibrates human worth to it, and builds a state that hunts “enemies” as a matter of routine administration. That separates it from generic ultranationalism, which may repress or expel but does not require genocide; from authoritarianism, which can be indifferent to race; and from imperialism, which pursues dominion but not necessarily racial metaphysics. The structure is the same one-way pipe of power; the content is a doctrine that decides who counts as human.

Racist

“Racist,” “bigot,” and “xenophobe” are often thrown as synonyms; they aren’t. Racism is a theory and a practice: it asserts a hierarchy of human worth tied to lineage or appearance and then treats people accordingly—individually or systemically. Bigotry is stubborn hostility toward a class of people—religious, sexual, political—that resists counter-evidence; it may or may not include a theory of hierarchy. Xenophobia is fear and hostility toward outsiders as such; it is about perceived foreignness, not a doctrine of ranked races. The term “semitism” by itself is a muddled antique; the live, precise term is antisemitism: hostility toward Jews as Jews, wrapped in myths about power, contamination, or conspiracy. One can be xenophobic without being racist (fear of foreigners of any race); one can be racist without being xenophobic (contempt for domestic minorities); one can be a bigot without either theory, simply by hating a group one was taught to hate.

Nation

Nation, country, citizen, and union describe different layers of belonging. A nation is a community of imagining: people who see themselves as a people through language, story, and fate. A country is the terrain plus the borders plus the institutions that govern it. A citizen is a legal member of the political community—entrusted with rights and obligations that non-members do not have. A union is a joining: sometimes of workers bargaining as one in the workplace, other times of previously separate political units covenanting to share sovereignty. Nations can spill across countries; countries can contain multiple nations; unions can be of nations or of states; citizenship is the key that unlocks the formal “we” of law.

Protest

Protest, civil disobedience, insurrection, terrorism, insurgency, and coup are all confrontations with power, but they differ in means, targets, and claims to legitimacy. Protest is the public expression of dissent inside the civic rules—marches, petitions, assemblies that announce “we object” without claiming the right to overturn the system. Civil disobedience steps across a line on purpose—nonviolent, open violation of a specific law to force a moral confrontation about that law’s injustice; it accepts penalty to dramatize the claim. Insurrection is violent effort to overthrow lawful authority; it refuses the system, not just a statute. Terrorism selects civilians as the instrument of communication; it is violence aimed at the uninvolved to send a political message. Insurgency is protracted, organized armed struggle to replace the regime in whole or part; terrorism can be one tactic within it. A coup is an internal seizure—actors inside or adjacent to the state (often the military) grab the levers in a single stroke; unlike insurgency, it does not build a counter-state, it just takes the one that exists.

Executive

Executive, legislative, judiciary, and military are not equal “branches” of the same kind. In a constitutional order the legislative writes general rules, the executive applies them to particular cases and runs the machinery, and the judiciary judges disputes and guards the fence lines. The military is force organized for external defense and, in healthy systems, kept under civilian executive control; it is not a lawmaking organ, which is why its intrusion is so destabilizing. Confusion among these roles is the acid that etches away checks and balances: when executives start writing rules, or legislatures run police, or generals dictate policy, the separation that prevents concentration begins to collapse.

Civil rights

Civil rights, human rights, civil liberties, the Bill of Rights, due process, and specific freedoms describe different shields. Human rights are status-independent claims—what no government may rightly do to any person: torture, arbitrary detention, disappearance. Civil liberties are the classic freedoms from government interference inside a particular constitutional order—speech, press, conscience, assembly. Civil rights are guarantees that you may participate as an equal—vote, access public accommodations, work and live without discrimination—so that liberty is not nominal for some and real for others. The Bill of Rights is one jurisdiction’s first list of liberties; due process is the promise that the state must follow fair, known procedures before it takes life, liberty, or property. “Freedom of speech” and “freedom of the press” are not the right to a microphone or applause; they are immunities from punishment for expression, subject to narrow limits like true threats or incitement. “Right to bear arms” is a particular institutional settlement about weapons and security; its scope is a debate about risk, militia, and modern technology, not a referendum on freedom in the abstract.

Corporation

Corporation, stock market, hedge fund, private equity, shell company, tax, tariff, income tax, and sales tax are parts of the economic engine, not stand-alone ideologies. A corporation is a legal person that can own property, sue and be sued, and outlive its founders; the stock market is the venue where slices of that ownership trade. A hedge fund is pooled capital granted broad leeway—derivatives, leverage, shorting—to chase returns; private equity buys control of firms, restructures them, and profits from resale or cash flow. A shell company is a paper wrapper with little or no operation, useful for simplifying transactions or, abused, for hiding ownership. Tax is compulsory contribution to the common purse; an income tax bites where you earn; a sales tax bites where you buy; a tariff bites when goods cross borders. Tariffs protect and raise revenue; they also invite retaliation. None of these words, by themselves, tell you whether a society is just; they tell you how resources and risks are being routed.

Monopoly capitalism

Monopoly capitalism, late capitalism, late-stage capitalism, Capitalist Realism, and end of history are diagnoses, not new systems. Monopoly capitalism points to markets where a few firms dominate, shaping prices and wages and politics. Late capitalism names a cultural moment when finance, branding, and platforms seem to pervade everything—work, leisure, identity—so that life feels drenched in market logics. “Late-stage capitalism” is the same phrase with more doom in the voice: a popular way to label grotesques and excesses as symptoms of terminal decline. Capitalist Realism is a claim about imagination: that it has become easier to picture ecological collapse than a credible alternative to markets. “End of history” is a claim about competition among systems: that liberal market democracies have no serious systemic rivals left; events still happen, but the category of “regime” has settled. Each term is a lens; none substitutes for looking at how power and property actually move in a particular place.

Social media

Social media, dark web, and dopamine describe the attention economy’s wiring, not its morality. Social media is the privatized public square, where algorithms allocate visibility according to engagement rather than truth. The dark web is a set of networks layered for anonymity; it shelters dissidents and criminals alike, reminding us that privacy is a shield used by saints and scoundrels. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that tracks reward prediction errors—“better than expected,” “worse than expected”—and helps train habits; it is not “the pleasure chemical,” and blaming dopamine for compulsive scrolling is like blaming a thermometer for the fever. The upshot is political: when speech, surveillance, and stimulus are managed by code you don’t vote for, the old civil-liberty fences need new posts.

Brain hemispheres

Left/right hemispheres are real anatomical structures with different specializations, though not the cartoon "logic versus creativity" split. Neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist argues (controversially—many neuroscientists find him too sweeping) that the difference is about modes of attention: the left hemisphere narrows focus to manipulate and categorize, while the right maintains broad contextual awareness.

In McGilchrist's model, the left hemisphere treats the world as composed of isolated, inert pieces it can grasp and use—it sees parts, not wholes. It creates maps and mistakes them for territory. The right hemisphere experiences the world as living, interconnected, and flowing—it sees relationships and contexts. Language sits mainly left, but meaning and metaphor need the right. The left names things to control them; the right understands that names never capture the whole.

This matters politically: A left-hemisphere-dominant culture might reduce citizens to data points, politics to procedures, and justice to rules applied without context. It would excel at bureaucracy but miss what makes communities cohere. A right-hemisphere awareness sees that democracy isn't just vote-counting but a lived relationship of trust, that rights aren't just words on paper but embodied experiences, that a nation isn't lines on a map but a web of stories.

McGilchrist's critics note that hemispheric specialization is real but more subtle—both hemispheres participate in most tasks, and individual variation swamps population-level patterns. The metaphor becomes dangerous when it excuses sloppy thinking ("that's just my right brain") or diagnoses entire cultures through neural just-so stories.

Use it carefully: as a lens for examining different modes of power (mechanical control versus organic influence), different types of knowledge (explicit rules versus tacit wisdom), different political temperaments (technocratic versus communitarian). Don't use it to sort people into boxes or pretend complex political problems have neurological solutions. The brain is integrated; so should be our thinking about power.

Gulag

Gulag, concentration camp, POW camp, and slavery are not interchangeable names for cruelty. Slavery is ownership of persons as property, totalizing control of labor and movement. A gulag was the Soviet system of forced-labor camps used to punish and exploit; guilt there was often political or invented, sentences were brutal, and mortality was staggering. A concentration camp is mass detention by category—ethnicity, religion, political class—often outside normal law; it ranges from lethal to “merely” crushing, and its essence is that individuals are treated as a problem set. A POW camp holds captured combatants under the laws of war; abuse is common in practice, but the category acknowledges status and rights. Precision honors victims and clarifies warning signs.

Whistleblower

Whistleblower, patriot, traitor, and conscientious objector are vantage words. A whistleblower breaks organizational silence to expose lawbreaking or harm; their loyalty shifts from team to principle. A patriot loves country enough to prize its ideals over its flatteries; sometimes that means obedience, sometimes warning. A traitor aids an enemy or betrays the political community; the charge is only meaningful where there is a genuine “we.” A conscientious objector refuses to kill on moral or religious grounds; this is not draft-dodging by clever paperwork but an appeal to a higher duty that accepts penalty. All four remind us that fidelity is not the same as compliance.

Prophet

Prophet, monk, warrior, pacifist, environmentalist, “tree-hugger,” artist, poet, journalist, lawyer, judge, author—these are roles, not arguments. They mark how a life is oriented: truth-telling that unsettles, devotion that withdraws, skill at disciplined violence in service of law or country, refusal of violence, care for the living world, creation of forms that bear meaning, reporting what happened, pleading a case, rendering judgment, making a record that outlives the news cycle. They are not immune to corruption; they are containers for aspiration. When politics gets hot, we start using the role words as praise or slur. Resist that flattening; ask what the person is actually doing with the role.

Music

Music, song lyrics, and protest song show how culture argues. Prose persuades by reasons; music persuades by memory and movement. A protest song is political speech carried on a melody that fits in your mouth; it recruits before it convinces and endures after the leaflets rot. That is not a flaw; it is how humans bind. If you want to understand a movement, read its white papers and its playlists.

The Russian Oligarchy

Russia's oligarchy emerged from a specific historical rupture: the collapse of Soviet state ownership created a vacuum that a handful of men filled by converting political proximity into economic dominance. The mechanism was privatization through loans-for-shares schemes in the 1990s—state assets worth billions transferred for millions to those with Kremlin access. These weren't entrepreneurs who built companies; they were insiders who captured companies.

The distinguishing feature: Russian oligarchs hold wealth at the state's pleasure. Putin demonstrated this with Khodorkovsky's imprisonment and exile—cross the president politically, lose everything. This isn't rule BY the wealthy but rule THROUGH selectively tolerated wealth. The oligarchs get rich by serving state interests (or at least not opposing them); the state gets a class of dependent billionaires who execute policy through "private" companies. It's a two-way leash: oligarchs need the state's protection from prosecution (their fortunes often have questionable origins), and the state needs their companies as instruments of power projection, both domestic and international.

The US as Oligarchy: The Case For and Against

The case that the US is oligarchic:

Money converts to political access through specific mechanisms. Super PACs (post-Citizens United 2010) allow unlimited spending on elections as long as it's "independent" of campaigns—a fiction everyone understands. Lobbying means those who can afford K Street firms get thousands of meetings while ordinary citizens get form letters. Revolving doors mean regulators come from and return to the industries they oversee. Policy outcomes correlate more strongly with elite preferences than majority preferences (Gilens and Page's 2014 study).

K Street is a major street in Washington, D.C., but the term has become a shorthand for the lobbying industry and its perceived outsized influence in American politics. It is often used with a negative connotation, suggesting special interests are prioritized over the public good.

The feedback loop: wealth buys policy influence, policy influence protects and expands wealth. Tax rates on capital gains stay lower than on wages; carried interest loopholes survive decade after decade; antitrust enforcement atrophied for forty years. The top 0.1% own as much as the bottom 90%—a concentration that translates into concentrated power over who runs, what gets coverage, which think tanks thrive.

The case that the US is not oligarchic:

Formal democratic mechanisms remain intact and occasionally bite. Elections still occur; upsets happen (Trump 2016, AOC 2018); popular movements sometimes win against moneyed interests (marijuana legalization, minimum wage increases). The wealthy don't coordinate as a class—tech billionaires fight finance billionaires fight oil billionaires. Multiple veto points mean even the rich struggle to get their way consistently.

More importantly: property rights aren't contingent on political loyalty. Bezos can own the Washington Post and criticize sitting presidents; Soros can fund progressive causes; Koch funded libertarian ones. The state doesn't assign wealth or revoke it for political sins. Markets, however distorted by lobbying and regulatory capture, still operate with genuine competition and creative destruction.

Historical Comparison: More or Less Oligarchic?

The Gilded Age (1870-1900) was MORE oligarchic than today. Senators were literally appointed by state legislatures often controlled by single industrialists. No income tax existed to redistribute. No SEC, no antitrust enforcement, no campaign finance restrictions whatsoever. Rockefeller controlled 90% of oil refining; Carnegie controlled steel; Morgan bailed out the US Treasury in 1895. These men didn't influence policy—they were policy.

The New Deal through Great Society era (1935-1975) was LESS oligarchic. Top marginal tax rates exceeded 90%. Union density peaked around 35%. Glass-Steagall separated banking functions. Strong antitrust enforcement broke up concentrated power. CEO pay averaged 20x worker pay versus 350x today. The turnover in the Fortune 500 was higher—established wealth faced more competition.

Today (2010-present) represents a partial return toward Gilded Age dynamics but with key differences. Wealth concentration approaches 1920s levels. But unlike the Gilded Age, formal democratic protections exist—voting rights (though contested), disclosure requirements (though circumvented), some regulatory apparatus (though captured). It's oligarchic influence through complexity rather than oligarchic control through ownership.

US versus Russian Oligarchy: The Distinction

The Russian model is oligarchy by permission—wealth exists at the state's discretion, revocable for political disloyalty. The state creates oligarchs by transferring assets and destroys them by prosecution. Property rights are conditional on political alignment.

The US model is oligarchy by accumulation—wealth accumulates through market dynamics (however rigged), then converts to political influence, which protects further accumulation. The state doesn't create or destroy fortunes directly but gets shaped by fortunes that emerge from nominally private processes. Property rights are robust regardless of political stance.

The test: In Russia, an oligarch who opposes Putin loses his assets. In America, a billionaire who opposes Biden or Trump keeps their assets but might lose a tax break. That's not a small difference—it's the difference between power over wealth and wealth as power.

Due Process: The Mechanism

Due process is the requirement that power follow its own rules before it can deprive you of life, liberty, or property. The mechanism: predetermined procedures that must occur between accusation and punishment. Not just any procedures—ones that give the accused notice of charges, opportunity to contest them, and a neutral arbiter. It's the difference between "the king decides you die" and "here's the specific law you allegedly broke, here's your chance to dispute it, here's an independent judge."

Two types exist: procedural (were the steps followed?) and substantive (are the rules themselves fair?). Procedural says even guilty people get trials. Substantive says even with perfect procedures, the state can't ban fundamental rights.

Where the US Currently HAS Due Process

Criminal trials for citizens: You get charged with murder, you get a specific indictment, discovery of evidence, right to counsel, jury trial, proof beyond reasonable doubt, appeals. The machinery might be underfunded (public defenders with 100+ cases) but the structure exists. Derek Chauvin got due process before conviction; so did O.J. Simpson before acquittal.

Civil litigation: Sue or get sued, both parties get notice, filing deadlines, discovery, motions practice, trial or settlement, appeals. The process might favor the wealthy (better lawyers, delay tactics) but procedures apply equally. Exxon and a corner store owner face the same civil procedure rules.

Administrative hearings: Lose your medical license, get deported, have benefits terminated—you generally get notice and hearing first. An ALJ reviews evidence, you can present counterarguments, decisions include reasoning you can appeal.

Property seizure with process: Eminent domain requires compensation. Tax liens require notice and opportunity to contest. Bank forecloses on your house through court proceedings, not by changing locks while you're at work.

Where the US Currently LACKS Due Process

Civil asset forfeiture: Police seize your cash claiming it's drug-related. You never get charged with a crime. The case becomes "United States v. $64,000" and you must prove your property innocent. Burden of proof reversed, no conviction required. In 2014, law enforcement took more through forfeiture ($4.5 billion) than burglars stole ($3.9 billion).

Drone strikes on citizens: Anwar al-Awlaki, US citizen, killed by drone in Yemen (2011). No trial, no charges, just executive branch decision he was an imminent threat. His 16-year-old son (also American) killed separately. The process: secret deliberation, no judicial review, no opportunity to contest.

No-fly lists: Your name appears, you can't board planes. How did it get there? Classified. How to remove it? Unclear. In 2014, the list had 47,000 names. The process for challenging inclusion didn't exist meaningfully until court orders forced creation of minimal procedures.

Immigration detention: ICE detains people for months without bond hearings. Children separated from parents with no tracking system (2018). Individuals deported while appeals pending. "Expedited removal" allows deportation without hearing if you can't prove you've been here two years.

FISA courts: Secret court approves surveillance of citizens based on government assertions. You never know you were surveilled unless criminally charged. 99.97% approval rate suggests the "neutral arbiter" isn't. Edward Snowden's revelations showed bulk collection without individual suspicion.

Plea bargaining coercion: 97% of federal convictions via plea deals. Prosecutors threaten decades in prison if you go to trial, offer months if you plead. That's not process—it's circumventing process through leverage. You have the right to trial like you have the right to buy a yacht.

Historical Comparison

LESS due process than today:

Slavery era (1789-1865): Enslaved people had zero due process—they were property, not persons before law. Fugitive Slave Act (1850) let any white person claim a Black person was escaped property; accused had no right to jury trial or to testify.

Jim Crow (1877-1965): All-white juries convicted Black defendants in minutes. Lynching operated as parallel "justice" system—6,500+ killed without trial. Scottsboro Boys (1931): rushed trials, no effective counsel, all-white juries, near-immediate death sentences for rape charges later proven false.

Japanese internment (1942-1945): 120,000 citizens imprisoned without individual hearings, charges, or trials. Military orders based on race alone. Korematsu challenged it; Supreme Court upheld it 6-3, later called it a grave error.

Red Scare (1919-1920, 1947-1957): Palmer Raids arrested 10,000 on suspicion of radicalism, deported hundreds without proper hearings. McCarthy era: careers destroyed by accusation, blacklists enforced without trial, "Are you now or have you ever been...?" became presumption of guilt.

MORE due process than today:

Briefly, Warren Court era (1961-1969): Mapp v. Ohio (1961) excluded illegally seized evidence from state trials. Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) guaranteed counsel for indigent defendants. Miranda v. Arizona (1966) required warning of rights. Brady v. Maryland (1963) mandated prosecution share exculpatory evidence. These years represent peak due process in American history—procedures actually enforced, not just proclaimed.

Today versus history:

We have MORE due process than the Gilded Age (bought judges, private police as corporate armies), than the Founding (only white male property owners fully protected), than Jim Crow (racial apartheid in justice).

We have LESS due process than 1965-1975 when Warren Court precedents were fresh, civil forfeiture rare, mass surveillance technically impossible, and plea bargaining less coercive.

The current era (2001-present) is characterized by due process in traditional spaces (regular criminal trials) but expanding zones where it doesn't apply—terrorism, immigration, surveillance, forfeiture. We didn't eliminate due process; we reclassified problems to evade it. Call it drugs, terrorism, or immigration, and suddenly the procedures become optional.

The tell: when the government really wants someone or something, it finds the zone where process doesn't apply. That's not rule of law; it's law as tool, deployed when convenient, circumvented when not.

The Banality of Evil: Arendt's Discovery

Hannah Arendt covered Adolf Eichmann's trial in Jerusalem (1961) expecting to see a monster. She found a bureaucrat. Eichmann organized deportation of millions to death camps not from bloodthirst but from careerism—he excelled at logistics, followed procedures, never personally killed anyone. His evil was thoughtlessness: he never considered what his efficiency accomplished, only whether forms were properly filed.

The mechanism Arendt identified: evil becomes banal when it's proceduralized. Split a monstrous act into small administrative steps, assign each step to someone who sees only their piece, and ordinary people will commit extraordinary horror while feeling no responsibility. The clerk who schedules trains doesn't load victims; the guard who loads them doesn't run gas chambers; the one who drops pellets follows orders from someone who never sees corpses.

The insight that terrified Arendt: Eichmann wasn't a sadist or ideological fanatic. He was a mediocre man who wanted promotion, avoided thinking about consequences, and hid behind "I was just following orders." The Holocaust required relatively few psychopaths but many bureaucrats who treated human destruction as a technical problem requiring efficient solutions.

Current US: Where We Exemplify Banality of Evil

Immigration enforcement machinery: ICE agents follow deportation quotas. Judges process 50+ cases per day via video link. Private prison contractors calculate profit per detained body. A child separated from parents becomes case number, not trauma. Each actor performs their limited function: the agent arrests, the processor processes, the judge adjudicates, the contractor warehouses. No one person cages children—the system does.

Drone strike kill chains: Analyst identifies "pattern of life" suggesting militancy. Targeteer develops strike package. JAG reviews legality checkbox. Pilot in Nevada pushes button. Damage assessor counts bodies via screen. Each follows procedure; no one murders. The 90% of drone deaths in Afghanistan that were unintended become "EKIAs" (enemies killed in action) by definition, not investigation.

Mass incarceration assembly line: Prosecutor threatens 30 years to force plea. Public defender with 150 cases recommends taking 5 years. Judge accepts plea in 3-minute hearing. Classification officer assigns security level. Guards enforce regulations. Parole board denies release per risk algorithm. Everyone follows guidelines; nobody asks if caging 2 million humans makes sense.

Algorithmic denial systems: Health insurance AI denies coverage per statistical model. Appeals processor confirms denial per protocol. Doctor fills out prior authorization knowing it's futile. Patient dies rationing insulin. Each actor optimized their function; the death is nobody's fault and everybody's.

Where We Resist Banality of Evil

Whistleblowers who break the chain: Chelsea Manning leaked evidence of civilian killings. Edward Snowden exposed mass surveillance. Reality Winner revealed Russian election interference. They saw their piece connecting to the whole and refused to be good bureaucrats.

Jury nullification: Twelve citizens can say "we don't care what the law says, this is wrong" and acquit. During Prohibition, juries regularly acquitted bootleggers. During Vietnam, some refused to convict draft resisters. The human conscience interrupting the machinery.

Sanctuary cities: Local officials refuse to be enforcement arms for federal immigration machinery. They see the faces, know the families, reject being intermediate steps in deportation pipelines.

Professional ethics enforcement: Lawyers who won't torture law to justify torture. Doctors who won't assist executions. Engineers who refuse to design weapons. Individuals asserting professional standards against institutional pressure.

US History: Worse Banality

Slavery bureaucracy (1789-1865): Auctioneers maintained price lists. Clerks recorded sales. Overseers maximized output. Doctors declared fitness for labor. Each performed their role in converting humans to property. The most extreme: breeding farms that produced enslaved humans like livestock, complete with ledgers and profit projections.

Indian Removal bureaucracy (1830-1890): Surveyors mapped territories. Treaty negotiators obtained "agreements." Soldiers enforced relocations. Agents distributed inadequate supplies. Boarding schools destroyed cultures child by child. The Trail of Tears killed 4,000+ through administrative process, not massacre.

Eugenics programs (1907-1970s): Social workers identified "defectives." Judges ordered sterilizations. Doctors performed procedures. Clerks filed paperwork. 60,000+ Americans sterilized via proper channels. Buck v. Bell (1927) upheld it 8-1: "Three generations of imbeciles are enough."

US History: Better Resistance

Abolitionists who saw the whole: Not just Underground Railroad conductors but those who connected cotton consumption to slavery, who refused to use products of slave labor, who made the invisible visible through witness.

Vietnam War resistance: Soldiers who refused orders. Draft board members who resigned. Pentagon Papers revealing the machine's logic. The bureaucracy disrupted by people who wouldn't be “good Germans.”

Nuremberg influence (1945-1950): Brief moment when America helped establish that "following orders" isn't a defense. That bureaucratic participation in atrocity is still atrocity. Before we forgot the lesson ourselves.

The Current Moment

We're neither at our worst (slavery, genocide) nor our best (brief post-Nuremberg clarity). We've professionalized the banality: algorithms make decisions, contractors execute policies, complexity obscures responsibility.

The tell: when something horrible happens, can you identify who decided it should happen? If the answer is "the system" or "the algorithm" or "department policy," you're looking at banality of evil. The family separated at the border, the patient denied treatment, the prisoner in solitary for decades—each is nobody's decision and everybody's execution.

The antidote Arendt identified: thinking. Not intelligence—Eichmann wasn't stupid. Thinking means asking what your efficient piece contributes to. It means refusing to be a desk murderer even if you never see blood. It means recognizing that procedural correctness doesn't equal moral legitimacy.

We're excellent at creating bureaucracies that produce suffering without identifiable villains. We're terrible at maintaining the kind of thinking that interrupts the machinery. Every generation discovers some past atrocity and asks "how could they?" while smoothly operating contemporary systems that future generations will ask the same question about.